By Peter Schlagel

The term umami has several different meanings which are often confused. This can generate much misunderstanding about how the umami effect works in cuisine and affects overall experiences of aromas and flavors in various kinds of food.

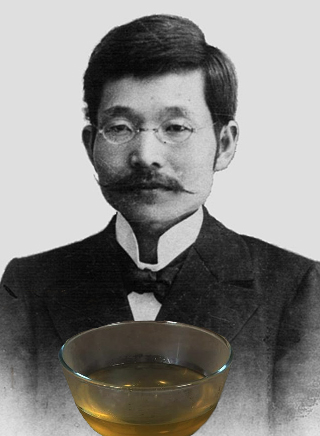

Umami was the name given in 1908 by the Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda who discovered its main active ingredient, glutamic acid (or glutamate), in a traditional Japanese tofu soup made from dashi kelp broth. He derived the name from the Japanese word Umai, which means both overall deliciousness and also the specific savory taste, and the Japanese word mi, which means “essential taste of”.

However, Umami as a distinct fifth basic taste was only recently verified by researchers in 2000 when they confirmed the existence of specific taste receptors in the human tongue for the primary umami chemicals, principally glutamate.

The apparent nutritional function of this basic umami taste in human evolution was to indicate food sources containing readily digestible proteins and amino acids. Umami has survival value.

Unlike other basic tastes like salty or sweet, umami does not have a simple singular taste of its own. By itself umami (and its main chemicals) tastes almost neutral or slightly sour or bitter, but it can greatly affect the overall taste and flavor of food. Umami enhances yumminess.

So how does umami work in making food taste better?

First, it is important to note that most of what we experience as the many flavors of the foods we eat and drink is directly related to our sense of smell and the many complex combinations of scents detected by our olfactory receptors. This basic olfactory sense is further complicated by how our individual brains and personal mental and memory experiences contribute to interpreting the signals received from smells.

These complex interrelations of basic tastes, olfactory signals and our subjective experiences change in complex ways over time as we consume foods. Umami is higher in foods at their fullest ripeness in the appropriate season. For example, unripe green tomatoes have low umami which increases as they ripen to a peak in full sun-ripened glory.

In addition to the basic primitive taste function of umami, there is also a synergistic and enhancing effect that results from the interplay of several different classes of umami chemicals. Adding ingredients from the same class gives an additive effect (e.g., 1 + 1 = 2), while adding several ingredients from different classes gives an intense multiplicative effect (e.g., 1 + 1 = 8). Umami interactions multiply flavors.

The key for this synergy is the ratio of glutamate to other umami ribonucleotides combined in different foods. This is reflected in well-known traditional combinations of ingredients in cuisines such as meat and vegetable pairings, tomatoes with aged cheese in Italian cuisine, Asian fish sauces, and savory meat broths. Let’s briefly review these core umami chemical classes.

First is the glutamate class (free glutamic acid and its more stable salt forms or glutamates). This was the first to be chemically identified in 1908 from soup broth. This is a naturally occurring chemical which is part of human digestion of proteins and amino acids needed by our bodies.

One familiar form of glutamate is MSG (monosodium glutamate) which, as a digestive source of necessary glutamate, is indistinguishable from other forms of glutamate naturally occurring in our bodies and involved in human digestion. While negative side-effects for MSG in some foods have been claimed (the so-called Chinese Restaurant Syndrome), modern research has shown this claim to have no factual basis in verifiable science.

Research instead suggests that a possible correlation with high levels of histamines found in much of Chinese cuisine has been misidentified with MSG as a cause of symptoms such as headaches in some people. Histamines cause allergic reactions in some people. As we know from good science, correlation is not causation. MSG is in fact both harmless and natural.

A second class is inosinate (or inosinic acid and its salt forms) which is chemically similar to glutamate. It is found naturally, however, in different food ingredients such as seafood (like bonito, tuna, sardines and mackerel, as well as prawns, mussels and oysters).

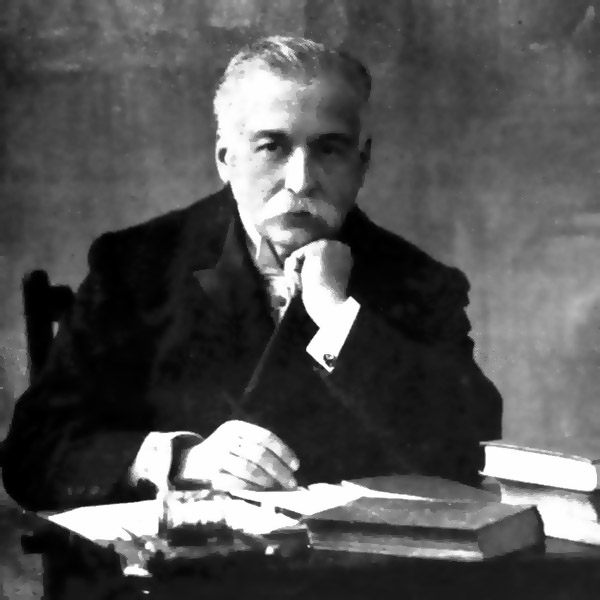

It is also found in certain meats (such as veal, pork and beef), as well as naturally occurring in human digestion. It occurs naturally in high quantities in dried sardines, bonito flakes and meat broth (such as those made famous one hundred years ago by the great French chef Escoffier).

A third class is guanylate (or guanylic acid and its salt forms) which is found naturally in high amounts in dried shiitake mushrooms. Drying further concentrates this natural umami chemical.

The human body also prepares for food digestion via signals sent to the brain along the vagus nerve pathway from both our stomach and pancreas where specialized cell receptors can also detect the presence of umami chemicals (especially glutamate). This complex process involves our tongue, stomach and small intestine, all under the overall direction of the human brain.

Another important factor which affects our enjoyment of food is our sense of smell which adds the complexity of aromas to the basic tastes. Also the sense of touch in our tongue and mouth gives yet another dimension of texture and temperature to flavor. And the intensity of what we experience, or the amplitude, is a quality for which umami plays a major enhancing role. The umami effect on our total food experience is subtle, complex, dynamic and synergistic.

In fact, the Japanese have another term to describe some of these more subtle qualities, kokumi, which refers to overall thickness in the mouth, flavor longevity, and a rich mouthfeel. Sources of kokumi include scallops, fish sauce, garlic, onions and yeast.

The chemicals which appear to be associated with kokumi are small tripeptides such as glutathione. While umami chemicals are effective at concentrations of parts per thousand, the chemicals imparting the greatest kokumi affects are found in concentrations of parts per million. Very subtle indeed!

In addition to the five basic tastes, our senses of vision and hearing play an influential role in our enjoyment of food. How food appears, its presentation, can greatly enhance or detract from the overall enjoyment of its other sensory qualities. Even sounds of cooking and eating can add to our delight in different foods – the crisp snap of fresh vegetables, crackling meat over the grill, and the low hissing of simmering savory soups can heighten our anticipation of good eating.

Finally, our state of physical health, our particular mood (whether anxious or relaxed, sad or happily excited), our past experiences and strong memories, and our cultural upbringing and heritage, all come together to affect the quality of our food enjoyment.

When we share a fresh tasty meal (including fresh shellfish and good wine, of course) and relaxed conversation with friends and loved ones we enhance our happiness and well-being. How we eat matters greatly.

Our basic senses of taste serve an important nutritional function as well as contributing to our enjoyment of food. When we have certain biological needs for nutrients we respond in different ways to their corresponding tastes.

Sweet indicates food for quick energy. Salty satisfies cravings for more minerals and thirst for liquids. Sour can indicate the need to boost metabolism with acidic and tart foods, as well as warn us of food that has spoiled (vinegar, rancid). Bitterness, which has a high sensitivity, warns us of substances that can be harmful. And it appears that umami indicates foods high in readily digestible proteins and amino acids.

A mother’s natural breast milk is one of the highest sources of umami. Thus there is an overlap between deliciousness and the healthiness of foods. The umami taste and its complex flavor enhancing effect can bring these worlds closer together so we can experience the greatest satisfaction in eating foods that are also the healthiest.

Learn How Umami Can Correct the Poor American Diet Tomorrow in Part 3

Presented at Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association 2014 Conference with many thanks to Taylor Shellfish Farms, Nikken Foods USA and Green Paper Products.

Your Culinary World Copyright Ana Kinkaid/Peter Schlagel 2014