By Ana Kinkaid

Once upon a time, there was an ancient dream - a story told over and over of a magic substance that when added to something found in everyday life would result in something wonderful, something amazing, something glorious.

Maier’ s Atalanta Fugiens, Emblem 8

Called an elixir, novels and operas have been written about it, philosophers have sought it and saints have claimed it. Kings and queens have offered diamonds and emeralds to ancient alchemists to obtain it.

Yet it was a perceptive judge, insightful chef and a determined scientist who finally found the substance that in food is the very essence of what ancients sought.

In 1793 there lived in France a young lawyer named Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, known simply as Savarin to the culinary world. Having earlier represented members of the nobility in legal matters, his loyalty to the French Revolution was in question and so was his life.

Like many of France’s intelligentsia, he fled to the new republic of America, whose recent revolution had been supported by French military training and the actual bullets fired at the final battle at Yorktown.

In America he taught French, played the violin in a Philadelphia chamber orchestra, studied medicine and chemistry and enjoyed roasting a turkey with no less a person than Thomas Jefferson at Monticello.

Monticello - Jefferson's Beloved Country Home

When Napoleon came to power, the extremes of the French Revolution were replaced with calm, making it safe for Savarin to return to France. Because so many lawyers had literally lost their heads during the Revolution, there was a great need for experienced lawyers such as Savarin in France. Upon arriving, Savarin was appointed the lead judge of the Court of Appeals, a court that evaluated the legality of laws, not individual cases, somewhat similar to our Supreme Court.

From the security of that position, which he held for the rest of his life, he wrote The Physiology of Taste. Published in 1826, two months before his death, it noted the presence of something special, beyond the four basic tastes of sweet, salty, sour and bitter, in soups, browned beef and the shellfish that he loved.

The Physiology of Taste - Never Out of Print!

He did not know what it was exactly, only that its presence made good foods taste fabulous.

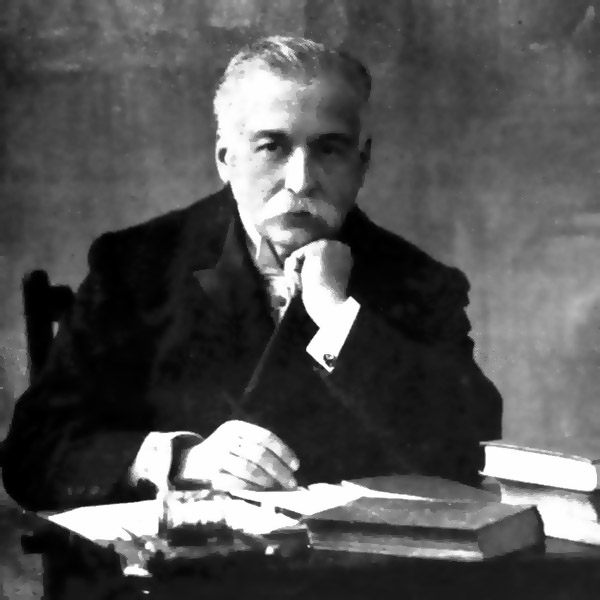

Nearly a hundred years would pass before another culinary great, Chef Auguste Escoffier, would seek the answer to what was the magic ingredient that made such a difference.

Born in France, he rose to fame as the “King of Chefs and the Chef to Kings” at London’s Ritz and Savoy Hotels.

There he rediscovered in 1890 that magic ‘something’ in his career-defining veal stock. In his legendary cookbook, Le Guide Culinare, he declares this stock, made from slowly browned bones and meat, as the core of the “Five Mother Sauces” on which all other French sauces are based.

When prepared correctly, each of these sauces has that certain something that makes French foods to what we define as “French Food.”

Yet at the same time, there was a young scientist, named Kikunae Ikeda, who lived in Kyoto, who was having dinner one evening with his wife and children. As is traditional in Japanese cuisine, the meal they were enjoying started with a warm cup of seaweed soup – the same miso based soup many of us have enjoyed when dining in a Japanese restaurant.

The soup they were sipping has long been part of Kyoto’s legendary Buddhist temple cuisine. The original recipe for the soup had come from China with the famed scholar Dogen, who was also the tenzo or cook at the Shojin Ryori Temple where no meat was ever served. Instead the cooks there turned to the richness of sea for flavor and protein.

It was that same mysterious rich full flavor that Ikeda asked his children to name. One said salty, another said beefy though there was no beef in the broth. It was Ikeda’s wife, who when it was her turn, described the core taste as “delicious!”

Miso Soup

Everyone laughed and said that yes that was the taste. But how can ‘delicious’ be a taste when the other four flavors of sweet, salt, bitter and sour are so defined? The question haunted Ikeda, who was an inquiring scientist as well as a thoughtful father.

It was one thing to know that the “deliciousness” exists, but Ikeda wanted to know exactly what it was and how it worked.

Soon he was researching what it was in the soup that made it taste so great. Years of trial and error followed. Bowl after bowl of soup was analyzed but the defining substance remained hidden, elusive. Yet Ikeda never gave up. Finally in 1908, he found the phantom element on his microscope slide.

At Long Last, There It Was!

Exhausted, yet excited, he wondered what to call his new discovery. Finally with a smile, he chose a name based on what his wife had originally given the taste – delicious essense or “umami” in Japanese.

Ikeda realized that his discovery had vast commercial application that could benefit humanity. If food was made more flavorful, more people would purchase and enjoy healthier cuisine. The result would be a reduction of disease through better diet.

He turned to a young industrialist, Saburosuke Suzuki II, who was successfully producing iodine from seaweed. And though Ikeda had found that sea kelp was a prime source for umami, Suzuki declined Ikeda’s request that he produce the new compound.

Now Available!

The long years of trial and error research had taught Ikeda not to give up easily. He finally convinced Suzuki and the magic product, long sought after by chefs and mystics, was available to the public.

Want to know what it is? That's tomorrow's story - Part II

Presented at Pacific Coast Shellfish Growers Association 2014 Conference with many thanks to Taylor Shellfish Farms, Nikken Foods USA and Green Paper Products.

Your Culinary World Copyright Ana Kinkaid/Peter Schlagel 2014